Hadicha Tanacheva, Salima Yakubova, Zahida Burnasheva, Ilkhamiya Tuktarova, Shafika Gasprinskaya – the names of these women are forever inscribed in the history of the Muslim community of Russia. It was they, active Muslim women, who were at the origin of the national women’s movement. Due to their initiative, women were allowed to go to mosques and get education after the All-Russian Congress of Muslim Women.

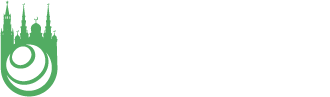

At the First All-Russian Congress of Muslim Women in Kazan, which took place on April, 24 of the year 1917, more than 72 participants, including the aforementioned people, and also about 300 other listeners raised issues of political and social inequality between women and men. The decisions taken as a result of the discussion were not only unprecedented for the entire Muslim world, but also progressive for European states. The participants paid special attention to women’s electoral rights, equal rights to work and take an active part in public life.

What was that Congress like? It was recognition of a Muslim woman’s place and role in society, her contribution to the development of culture. It was women who headed large national schools, madrasas. They took part in journalistic activities, they published magazines and newspapers in the Tatar and Russian languages (magazines “Il’” (Country) and “Koyash” (Sun) and magazine “Söyembikä”), where there was information about the preparation and holding of the Congress, public reaction to its decisions. Writers, poets, stage artists, performers and vocalists appeared –all that had happened before the revolution. The Women’s Congress was the force that determined further prospects of Muslim peoples of Russia in general and the Tatars in particular.

The All-Russian Congress of Muslim Women in Kazan, 1917/arhiv.tatarstan.ru Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

The first Aitova’s secular school for Muslim girls

It is important to note that the role of Tatar women in the consolidation of the women’s movement was crucial. One cannot overestimate that exorbitant contribution to the preparation of the Congress and the agenda-setting made by teachers. One of them was Fatiha Aitova, an outstanding educator and teacher, the head of the first secular school of the European level for Muslim girls in Kazan, which, unfortunately, existed only till the year of 1918. It was she, who established a handicraft school for girls in Sukonnaya Sloboda.

On August, 16 of the year 1909, Aitova appealed to Pinegin, the Director of folk colleges of the Kazan Province, for permission to open “a female mekteb for teaching Tatar girls Muslim religion, the Russian language and Russian literacy according to the programme of primary schools”. She got permission and the school opened officially on August, 27 of the year 1909. For the most part, the funds for the maintenance of the school were given by Aitova herself. A small part of money was given by pupils’ parents. And already since 1910, the school commission of the Kazan City Duma provided the school with the money in the amount of 600 rubles.

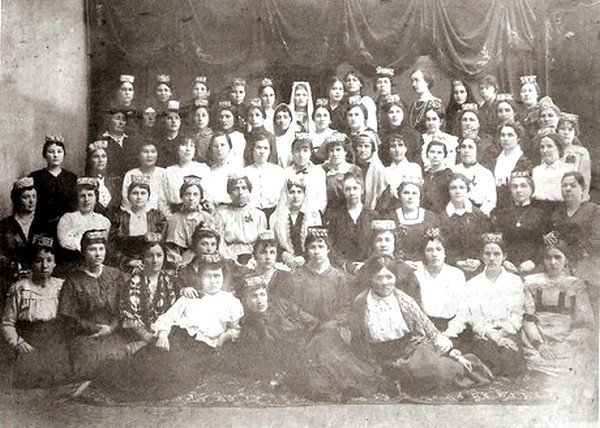

During the first year, 85 girls, residents of Kazan, graduated from the school. Later the number grew because there appeared pupils from other cities. In 1911 there were already about 120 pupils. In 1913-1914 there were five classes in school. In all those classes there were parallel departments, where 220 girls studied.

Pupils of Fatiha Aitova’s school / Public Domain

Pupils of Fatiha Aitova’s school / Public Domain

During that period of time, nine female teachers worked in Aitova’s school: seven in number of classes, a teacher of Russian and a teacher of needlework. Russian and needlework were taught by Russian teachers Ievleva and Moiseeva. One of the Kazan officials wrote to the Minister of Internal Affairs on November, 26 in 1913: “This school is the only one of its kind both in terms of participation of Russian teachers along with Muslim teachers and the uncertainty of the teaching programme”. The following subjects were taught at that school: Doctrine, the Tatar language and Literature, Arithmetic, Geography, History, Environmental Studies, Penmanship, Art, Needlework and Russian. Also at the lessons of the Russian language such disciplines as Russian History and Geography of the Russian Empire were taught. The rest of the subjects were conducted only in the Tatar language.

In the process of trying to open the school with the eight-year education, Fatiha also applied to the Guardian of the Kazan District, but without success. Having failed in Kazan, the woman made up her mind to go to Petrograd. Already there she decided to ask a State Duma Deputy from Kazan Ivan Godnev for help. And after long paperwork on March, 4 in 1916, Fatiha Aitova got the Guardian’s permission to “open a private secondary school for Muhammadan girls in Kazan <…> with the following conditions: that the school applies only those educational guidelines that have been approved by the Ministry of Public Education and the spiritual leadership of the country, that teachers are elected from among those who are legally capable, that Russian Literature is introduced into the number of subjects taught in the projected school”.

The grand opening of the Tatar female gymnasium took place a bit later, on October, 29 in 1916, where representatives of the local administration, Governor Boyarsky, Mayor Boronin, Guardian of the Kazan school district Lomikovsky, Director of folk colleges Vasilyev, Chairman of the city school commission Grauert, officials of the school district, and members of the school commission were present.

The Mullah’s wife, Muhlisa Bubi, and her enlightenment efforts

Special attention is drawn to the personality of Muhlisa Bubi. Her life’s work was the education of girls, creation of the educational complex for that goal on the basis of the old Bubi’s madrassa for upbringing and education of the youth. Bubi’s family established a complex of educational institutions, including the male madrassa with eight-year educational programme, the eight-year female madrassa and the four-year primary school. It is worth mentioning that it became the first place for the Tatar people, where they could get secondary secular education in their native language. Besides, it was also the place, where male and female teachers were trained for Tatar schools with new methods of teaching.

Muhlisa also studied theological sciences, following the programme of the male madrassa under the guidance of her brothers. By 1905 she had become a highly educated woman, who perfectly knew the Islamic doctrine. The brothers fully entrusted their sister with the management of the women’s teachers’ seminary. The fact that Muhlisa was called “the Mullah’s wife” became the recognition of her authority as the head of the madrassa and a scholar of theology.

Muhlisa Bubi / islam-today.ru

Muhlisa Bubi / islam-today.ru

As far as the madrassa curriculum is concerned, the main subjects were Theology (including basics of the Muslim Law), the Tatar language and Literature, the Russian language and Literature, Mathematics. In addition to it, the following disciplines were taught: the Arabic language, Geography, Science, Pedagogy and Methods of teaching, Calligraphy, Art, Home Economics and Needlework.

In 1905-1908, in conjunction with the school there began to open pedagogical colleges and also it was allowed to take exams and issue certificates of awarding the title of a male or a female Muslim teacher. Certainly, the certificate was the official document recognized by the administrative bodies of Russia.

In 1914 another female madrassa was opened and simultaneously there was got permission to open a female teachers’ seminary. Muhlisa Bubi became the head of that seminary and in that position she was elected to the post of the Qadi of the Spiritual Administration of Muslims.

Her contemporaries described her as a well-read woman, who fluently spoke the Tatar, the Arabic and the Persian languages. She gained a lot of respect in the area. Muhlisa Bubi was actively involved in the work of the Central Spiritual Administration of Muslims. The cases related to family proceedings were identified as her terms of reference. At the same time, the Central Bureau of Muslim Women was active in establishing women’s committees. It happened not everywhere. In the European part and in Siberia new women’s committees were established in many villages, but in the Caucasus and in Central Asia – only in few cities. The committees of Muslim Women sent out female and sometimes male lecturers to explain the decisions of the Moscow General Muslim Village Congress and set up leaflets and fundraising.\

The All-Russian Congress of Muslim Women in Kazan, 1917 / arhiv.tatarstan.ru Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

The All-Russian Congress of Muslim Women in Kazan, 1917 / arhiv.tatarstan.ru Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

The main idea of all her work for the benefit of the Russian Muslim Ummah was the belief that Muslim women could and had to reach the equality with men, while maintaining morality and not violating the precepts of Islam. She told about it in one of her articles “Woman in the Islamic World”: “The number of women serving the great cause of rooting Islam in the world with the help of knowledge is not in the tens, but in the hundreds”.

If we are talking about educational institutions of those times, then we should tell about the school of Lyabiba Khusainova, which was the second, after Bubi’s school, large comprehensive school for girls in the pre-revolutionary period. It was recognized by the Soviet government, which equated it with secondary schools. Those people who graduated from that school were awarded the title of primary school teacher by the decree of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and the USSR Council of People’s Commissars on the introduction of personal titles for teachers dated April 10, 1936.

In addition to her own school, Lyabiba also organized some sort of refresher courses for its teachers. The classes were conducted by the teachers of madrassa “Muhammadiya” in the evenings at Lyabiba’s school. The work of the courses was kept in a great secret both from the educational authorities and the Tatar population, because the discovery of the classes would cause trouble for school. Senior schoolgirls, who were going to devote themselves to the teaching career in the future, had practice in junior grades.

Lyabiba Khusainova’s biography is very interesting and diverse. But we would like to mention one interesting fact, which most clearly emphasizes her level of education and thought. In February of the year 1911, Lyabiba received a certificate of the Orenburg Spiritual Assembly, which gave her the right to teach in the Tatar women’s school. It was made in order to preserve the school: since 1910 all the school with new methods of teaching began to close as they did not have special permission from the educational authorities. And the permission was given only to those people, who had at least a certificate of the Spiritual Assembly. Those certificates were mainly given to men, who graduated from a madrassa. Lyabiba Khusainova was one of the few women, who got it.

Sara Shakulova in charge of technical and vocational education for girls

The activity of another participant of the All-Russian Congress of Muslim Women, Sara Shakulova, is not less interesting. All her life she worked in the sphere of public education: she taught Mathematics in Zaraysk College of Ryazan Province (1915-1916), in Kazan City Women’s Commercial School Eckert (1916-1919), in Fatiha Aitova’s Tatar school for girls and in Lyabiba Khusainova’s women’s school. In 1919-1923 she was Deputy People’s Commissar of Education and Head of the Main Department of Vocational Education of the Bashkir ASSR. “Shakulova put a lot of work and energy into raising cultural level among Bashkir workers, especially in the terms of vocational education… With her direct and active participation, there were organized several vocational educational institutions (agricultural, pedagogical, agricultural machinery repair, etc)” – it can be found in one of the characteristics.

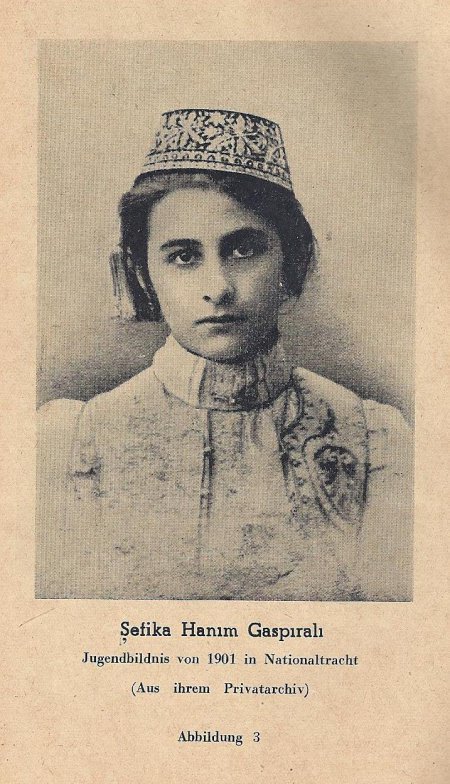

Shafika Gasprinskaya about the harmony of secular and religious

In 1906 another young girl graduated from the lyceum. She was destined to contribute to the development of female education. Her name is Shafika Gasprinskaya. In the same year, immediately after her graduation, Shafika became the head of the editorial office of the first in the Muslim world women’s magazine “Women’s World”, which initially was the appendix to “Terjiman”. “Women’s World” was a special weekly scientific and literary magazine, the main purpose of which was spiritual development and education of women at the time. The programme of the magazine for Crimean Muslim women was approved in Saint Petersburg and it comprised such issues as government regulations and laws concerning women, practical advice on housekeeping, family and children’s hygiene, issues of domestic work: needlework, weaving, sericulture, stories about lives of women in different countries, biographies and portraits of outstanding women around the world, tales, letters from readers, scientific discoveries, inventions, literary news, announcements and advertisements.

Shafika Gasprinskaya/Public Domain

Shafika Gasprinskaya/Public Domain

It was she who proposed a programme of actions to improve socio-economic and public state of women, which consisted of 14 points. Shafika told about the necessity to leave behind those customs that were a visible example of humiliation of women’s honour and dignity. In addition to it, she called for a ban on the marriage of girls under the age of 16. Opening hospitals, pre-school institutions, schools for girls – were the things, which Shafika Gasprinskaya always spoke about. It was largely due to her endless work there was made a decision to establish the Crimean Central Muslim Women’s Committee. Besides, there were formulated the main objectives of her activity, which include, for example, recognition of all human rights of Muslim women, broad propaganda of democratic ideas, dissemination of knowledge necessary for participation in public and political life, inclusion of as many Muslim women as possible in the conscious demand and exercise of rights both in family and in public and political life, protection of women’s rights and cultural and educational activities among the general public.

“Women, who take part in the movement, should be highly educated, tolerant and have heart full of love for their native land and people” – Gasprinskaya highlighted it in her speeches.

As far as the work of the Committee is concerned, all its forces were aimed at introducing maternity and childhood protection, facilitating the entry of all the Muslim women into all the spheres of public and service life and holding various events. In the middle of August of the year 1917, a three-day Regional Women’s Congress was held in Crimea, where Shafika Gasprinskaya read the main report and reminded about the necessity of studying own rights in Islam in order to successfully and as soon as possible overcome discrimination. Already in November she was elected the First Kurultai Delegate of the Crimean Tatar people of the Eupatorium County.

“Women should take active part in the elections of Kurultai Delegates and its work. For tomorrow’s sake, we must work now”, - Gasprinskaya stressed in her address to the colleagues.

Ilmira Gafiyatullina